One of the end of day rituals I most clearly remember growing up was the process of mixing and setting a bowl of yoghurt for the next day. I forgot about this little tradition for a while when I started living on my own after graduating and starting my own design practice. Supermarket-bought commercial brands of yoghurt made going through the motions of setting one’s own seem quite pointless and not worth the effort.

I eventually did start setting my own yoghurt, since I realised that the two quantities I would get at my supermarket would always end up being way too much or too little for my day to day usage.

Before we dive into the nitty-gritties of setting yoghurt, I’m going to quickly cover what the whole process entails, from a biological point of view. The conversion of milk into yoghurt is the work of a few varieties of Lactobacillus bacteria. They basically consume the lactose (the disaccharide sugar present in milk) and convert it to protein and lactic acid. The lactic acid is what gives yoghurt its characteristic tang. I think different strands or varieties of Lactobacillus produce subtly different varieties of yoghurt. I’d recommend purchasing a small quantity from your local dairy or from a restaurant that serves fresh, nice tasting dahi on the menu, the best of which I’ve come across have been in Udipi restaurants. All you’d need to “acquire” would be about a teaspoon’s worth. I’d recommend taking a little zip-lock bag with you the next time you visit an Udipi restaurant. Bag some like you’re secretly bagging forensic evidence. Good luck with that.

I tried using commercial varieties, but I’m pretty sure they add pima and other thickening agents to it, which ends up giving you very flaccid and unhealthy looking yoghurt. The variety of Lactobacillus they use (and this I found in more than one brand) results in a terribly slimy, stringy sort of yoghurt. This happens because the bacteria (the particular variety they use) exist in long strands, or have elongated polysaccharide complexes along their outer casing.

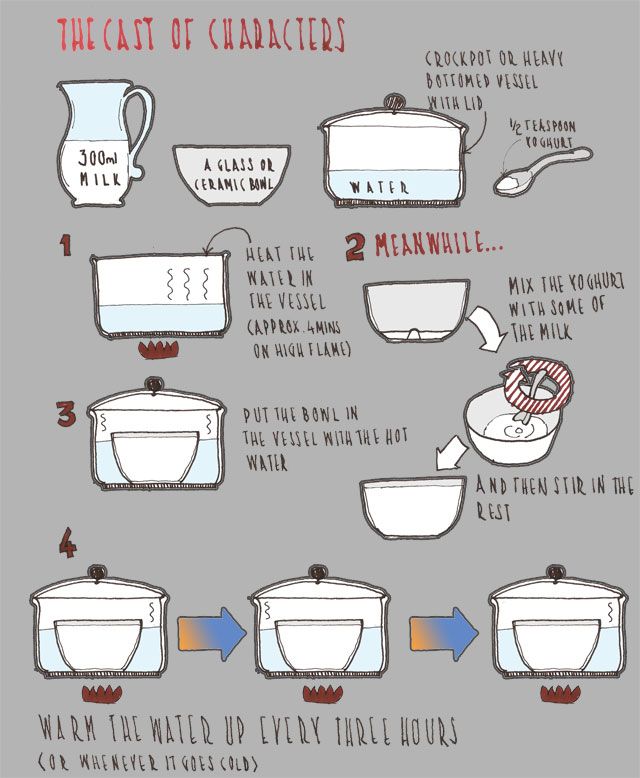

I put about 300ml of milk to set overnight. This is how I do it:

The list of needed items is quite small. You need:

300ml milk (toned/whole milk, whichever your arteries prefer)

½ teaspoon yoghurt (dairy-bought or from a restaurant, keep in mind a lot of restaurants use commercial yoghurt, that’s not the type you want)

Ceramic or glass bowl.

Crock pot or any heavy bottomed vessel big enough to contain the bowl with space to spare; should have a lid.

Water.

Put the empty bowl in the crock pot or vessel and fill the space outside the bowl with enough water to bring the water level just about a quarter inch below the mouth of the bowl. Remember this quantity of water so you won’t have to measure it this way every time you do this.

Heat the water to scalding temperature (this is exactly what it sounds like..not hot enough for it to bubble or boil, but hot enough to make you want to pull your finger away quickly when you dip it in the water). Once you put the water to heat, spoon the half teaspoon of yoghurt into the bowl, with a few tablespoons of the milk. Stir or whisk the little lump of yoghurt into the milk with a small spoon till its completely dissolved. Pour in the rest of the milk and stir. Place this in the hot water bath inside the crock pot or vessel and close the lid.

I recommend a heavy bottomed vessel to retain the heat a little longer than usual. Be careful not to get the water too hot, because that might end up killing the bacteria or scalding your fingertips when you place the bowl of milk-yoghurt mix into the vessel.

Let this sit for around 8-10 hours. Re-heat the water when it cools down in a few hours. The warmth keeps the Lactobacillus cosy and warm so that it does its job extra quick.

I usually mix the solution up around midnight, wake up in the morning and re-heat the water around 8 or 9 am and put it in the fridge to set around 10 or 11. Yes, I know that amounts to nearly half a day of setting, but I always have curd that’s practically thick enough to cut with a knife.

A few more tips:

- Do not use more than the specified quantity of “seed culture” (the half teaspoon of yoghurt). This will not speed up the process they way you’d want it to, it’d just result in an overfermentation with the Lactobacillus multiplying to much too soon. Think of a slowly filling up theatre for a play and an overcrowded, busy train station…which do you think would smell better?

- The warmth is what keeps the process active, even in places where the temperatures drop well below 20°C. I heat the water up more often during the winter months. Too much heat will kill the bacteria and cook the yoghurt, so keep an eye, or a fingertip in this case, on the temperature.

- Pick the initial strain from a restaurant or dairy where you like the taste of the yoghurt. Udipi restaurants serve it set in little vessels, so you know that its freshly set, not spooned in from a tub of commercial yoghurt.

- Run a knife through the yoghurt before you spoon it out of the bowl, if you’re looking for those large, chunky, iceberg-like blocks of yoghurt.

- Using warm milk does help speed up the process.

6 comments

Jahnvi says:

Jun 1, 2011

Hi Anand,

This is a great step-by-step guideline on how to make Dahi. Ironically enough, in the States I tried to set dahi ONCE and it ended up being horribly sour. After reading your post, I think I can finally figure out what I did wrong – used too much starter, and the milk was probably not hot enough.

From experience in lab, most bacteria love 37C to 42C temperatures to grow. 37C is close to body temperature so technically when you touch the milk it should feel luke warm as opposed to scalding. But clearly your method works and mine doesnt! So there goes my scientific knowledge / logic. Perhaps this strain of bacteria prefers much warmer temperatures?

Anyways, fantastic post. I love the cast of characters visual. Really adorable.

Back to the temperature of water / milk, I do have a nerdy request though – since we are getting all scientific – do you think you could measure the temperature of the:

a) water bath you place the bowl with milk + starter in

b) milk

I feel like this will nail the process for me. Everyone always has their own description on how hot or cool the milk / water bath should be. Its so arbitrary and I clearly dont have the magic touch or the skill. 🙂 Pretty please?

qfactor says:

Jun 1, 2011

Yup, I totally intend to. The only reason I haven’t already is because I don’t have a thermometer.

I plan to get an oven thermometer though, sometime this week. I suspect my oven’s thermostat isn’t calibrated properly, thanks to which I always get overtly crusty bread.

I think I’ll have to figure out where I can get a standard lab thermometer, or one of those fancy digital ones which you point at things to get temperature readings.

I’ll also need to figure out a way of giving active references for all the folks reading this who might not have a thermometer to take accurate readings off.

Pat says:

Jul 20, 2011

It’s ironic that I’ve stumbled upon your page with this recipe as I was just told how to do this by my son’s Dr.He is recovering from a horrific auto accident in September and we were discussing the pros and cons of yogurt and probiotics since he has had large amounts of antibiotics. Thanks!

Anand Prahlad says:

Jul 20, 2011

I’m glad you did stumble upon this. I hope he recovers speedily.

Whole cream milk sets faster and thicker, thanks to the greater lipid content. People usually react to whole milk rather negatively, assuming it’ll contribute to weight gain, but this is not actually true. Studies show that people put on more weight from skimmed milk rather than from whole milk. I think its higher calcium content also would help the healing process positively.

Jagdip Rana says:

Sep 23, 2011

I also stumbled upon this post while I was looking for perfect way to set dahi at home. Great post ! Anand we are waiting for more details about temperature etc. Please work it out ! I request every one else to record their experiments/experience with dahi making. If we work out a “standard” process it will be really be a great contribution !

Ulf says:

Jun 24, 2012

When I was a kid who made yoghurt at home every day, the way I measured temperature was by placing few drops of milk on the back of my hand. It should be warm, but slightly less than hot. Vague, I know, but once you get it right, you’re set. Like yoghurt.