There are few things as primordial and “back to roots” as the act of making bread. Its a very scientific process, with exact measures and proportions for everything that goes in it and it also calls for a certain degree of skill when it comes to kneading the dough to just the right consistency. There’s also a special pleasure in breathing that fresh bakery like aroma when the first whiff of baking slowly fills the air, a few minutes after the dough is put into the oven.

So far, I’ve tried making two varieties of bread, one that required some fancy kneading, and another easier, no-knead variety. The latter is the one I’m going to elaborate upon in this article, since I think its not very messy or complicated and is a good option for a first attempt at breadmaking.

Sally Lunn bread has a history dating back to the late 1600s in England. Sally Lunn wasn’t actually a real person, but the name is rumoured to have come from either a French Protestant lady named Solange or from “soleil et lune”, sun and moon, thanks to the buns they were shaped in and their yellow inside colour. Egg yolk gives it that special yellow colour.

There are two main reasons why I think this is a good first step towards breadmaking. Firstly, it isn’t messy to assemble. You can mix the whole thing like cake batter in one mixing bowl with a wooden spoon. No need to get your hands all messy kneading sticky dough on a floured up counter that would need cleaning later. Secondly, there is a special stretchy consistency that you need to achieve when making any sort of bread, and you’ll see it here when you add all the flour to the mix.

We in India are used to seeing dough as this solid, heavy lump when we’ve seen it being kneaded to make rotis, chapatis and other flatbreads. When I first tried to make another variety of bread that needed kneading, I kept adding flour to counter the super stickiness of the dough, which eventually made the bread not as soft as I would like it to be. Bread dough is considered ideal when it reaches an almost elastic consistency, where something called windowpaning can occur. Windowpaning involves pinching off a small ball of the dough and stretching it between your thumbs till it becomes translucent (like a windowpane). You’ll see the dough reach this exact consistency towards the end of mixing phase of this recipe. This will be a much stickier and wetter dough; the consistency of the final baked bread is actually more cake like.

This is an adaptation of a recipe from Smitten Kitchen, which she has in turn adapted from other sources. Hers is a quicker method; mine spreads over two days, with the preparation of the dough in the latter part of day one, with an overnight rise and an early morning baking, just in time for breakfast. So here goes:

Sally Lunn, or Soleil et Lune bread

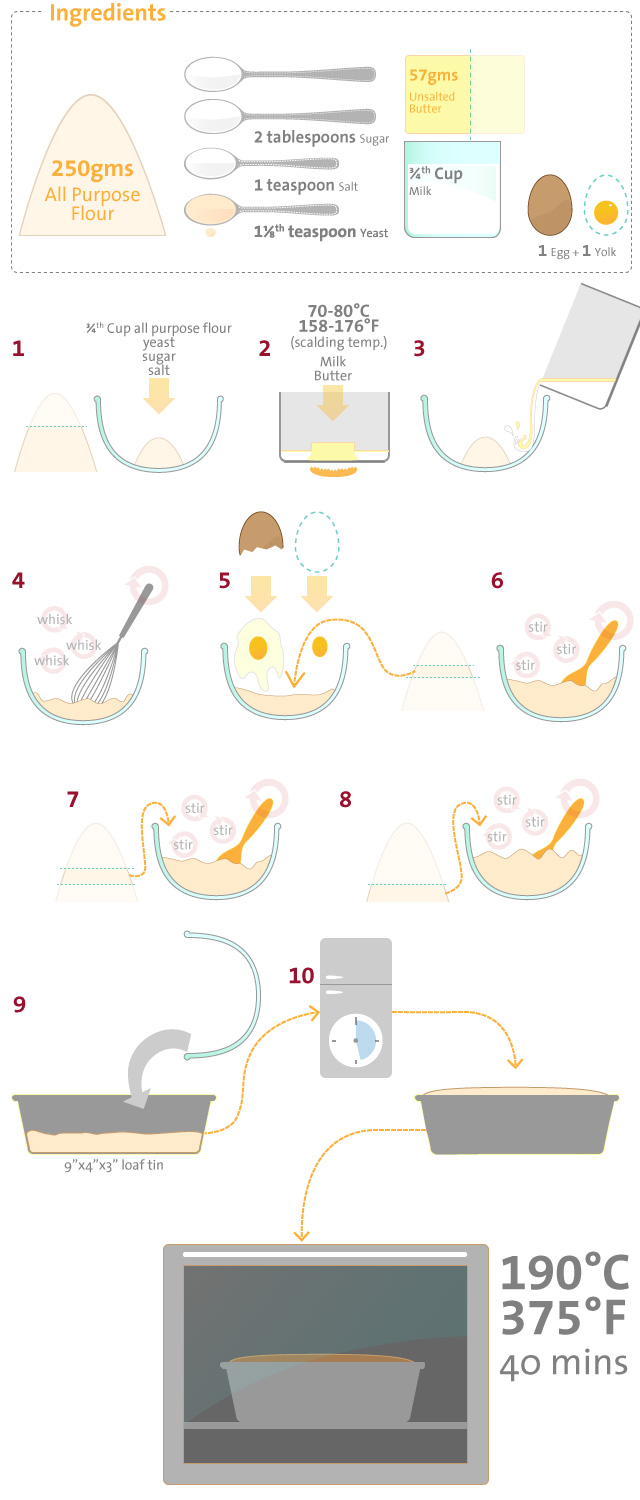

Ingredients

250gms (2 cups or 8.75 oz) all purpose flour (maida)

2 tablespoons (25gms or 0.875 oz) granulated sugar

1 teaspoon (5gms or 0.175 oz) salt

1 1/8 teaspoon (3.5gms or 0.125oz) active dry yeast

3/4 cup (177 ml) milk

57gms (4 tablespoons or 2 ounces) unsalted butter

1 large egg plus

1 small egg yolk (can leave this out if you fear an eggier bread)

A note about the units of the measures first. I’ve listed the quantities in the most easy and accurate to measure format. For example, you’re better off weighing out 250gms of flour rather than scooping it in a cup measure and then tapping it till the flour settles, though its easier to measure a teaspoon of salt rather than give yourself a stroke trying to weigh 0.175 ounces of it (especially if you have a mechanical weighing scale like mine).

Measure out one third of a cup of the all purpose flour or maida into a large mixing bowl. Add the yeast, sugar and salt to it. I use a whisk at this point to give the mixture a good whisk till everything is evenly distributed in it.

Put a heavy bottomed saucepan with the butter on a very low flame. Let the butter melt; I would recommend holding the saucepan above the flame to keep it from sizzling or browning. You don’t want to make ghee of it. Pour in the milk just before the butter goes completely liquid to make sure this doesn’t happen. Let the saucepan sit for a minute on the flame. You don’t want the milk getting too hot, as it will kill the yeast. I usually check the temperature by sticking a butterknife into the liquid and quickly touching it to my skin. It needs to be a touch above lukewarm, well under scalding temperature. If the milk-butter emulsion (since we can’t call it a mixture because melted butter and milk don’t really mix) is too hot, let it sit for a while till it reaches a healthy temperature. I’d guess 50°C, but I wouldn’t recommend this value before I confirm it with a thermometer, which I don’t have yet.

Pour this into the dry ingredients in the mixing bowl. Use a whisk to stir it evenly till there are no lumps left. Don’t whisk, stir. Its easier to use a whisk than a wooden spoon or ladle because it takes care of the more stubborn lumps much quicker this way.

Crack the egg into the mix, add an extra yolk here if you’d like your bread to be a nice golden yellow. Some folks might not fancy the extra eggy taste to the bread, so you could leave the extra yolk out at this point. You’d just get a slightly whiter bread this way.

Put all the remaining maida/flour into a sieve and sift about a third of it into the bowl. Use a wooden spoon now to give it a good stir, till it looks nice and smooth. Sift in the remaining flour in two lots and stir.

You’ll see it reaching the stretchy elastic consistency by the first addition of flour after the eggs.

Keep stirring till the mixture is evenly blended with no lumps.

Lightly butter and flour a 9″x4″x3″ loaf tin. I usually butter the thing first and then drop a tablespoon of flour and tilt it around till the flour evenly coats the tin. You could blow it around a bit too, so that it coats the entire inner surface evenly.

Pour the dough mix into the loaf tin and use the wooden spoon or spatula to spread it evenly along its length. Doing this ensures that the dough rises evenly, you’re looking more for a vaulted surface than a domed one once it has risen fully.

Stick this in your fridge and leave it overnight. The slow fermentation and lower temperatures should help gluten form and keep the thing from collapsing when you finally put it in the oven.

The next day, the dough should have risen about half an inch or so above the edge of the tin. If its still not risen enough (this might happen if you put the dough in too late in the night and it hasn’t had enough time to rise), put the batter and tin out in the morning sun (and only morning sun as any other declination is going to over ferment the bread or kill it) or in a warm place till it reaches the right level of rise. To keep the surface from drying out, I usually coat the surface with melted butter, using a pastry brush. You could also oil a shrinkwrap plastic sheet and cover the tin with it.

Preheat your oven to 190°C (375°F). Once preheated, bake the dough for 40 minutes with the tin placed on the lower third of your oven. This usually results in a nice crunchy dark crust, but if you don’t fancy too much of a crust, you could turn off the upper heating element of your oven (if that’s the sort of oven you have) after 25 minutes, or whenever it reaches the dark golden brown colour you want it to reach.

Once done, overturn the bread onto a cooling rack and let it sit for five minutes at least before slicing up and consuming.

Do give this bread a shot. My description might be verbose, but it is a very simple recipe with easily available ingredients and isn’t too much of a pain to assemble. The end result is this soft, light and very fluffy bread that is just perfect for breakfast.

5 comments

Revati says:

Jun 1, 2011

When I get me an oven, we shall make Goan Sun Baked Sally Lunn Poi. muuhuhahaha!

Vivek says:

Jun 3, 2011

The illustration style is awesome man.. great work..

Shaheen says:

Jun 9, 2011

4-6 is especially adorable!

Anand Prahlad says:

Jun 9, 2011

Thanks Shaheen :).

I just baked another round of this bread this morning to re-check the recipe. I put up pictures of it here:

https://www.facebook.com/media/set/?set=a.125678537513614.31222.123276177753850

They’re not so fancy, phone-cam pics, else I’d have put them up here too.

Sunil Baindur says:

Apr 24, 2012

This is really inspiring Anand. Love the simple , yet apt illustration.

Superb!