The original illustration of da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man lies in the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice. It is drawn on a sheet of paper of a size similar to a standard A4 paper. The drawing is practically etched into the paper with (I assume) a bow pen. Tiny details and flaws, like smudged ink at the figure’s feet and the small overlap where the compass completed the circle are testament to the hand drawn and minimally mechanical nature of the drawing.

It is assumed that da Vinci drew the figure in brown ink on a buff sort of paper, but I’m pretty convinced the original illustration was a pristine black ink on white paper drawing. The black ink from my pen, the one I sketch with, also turns brown as it ages, though it’ll take another half millennium to see if they turn as brown as the original.

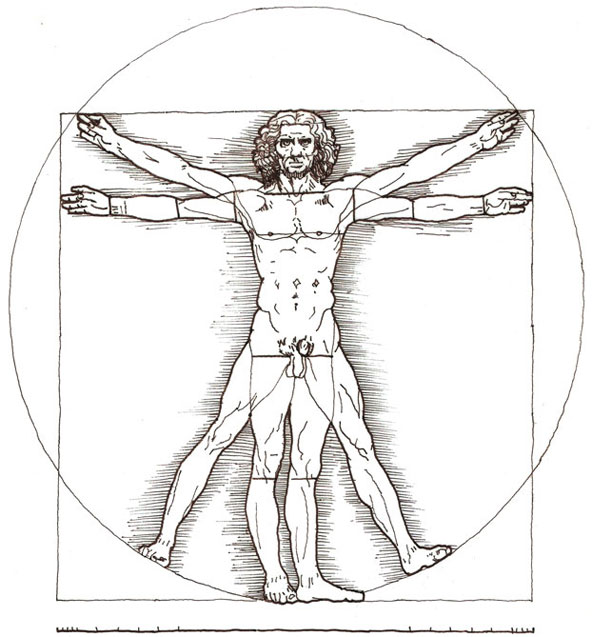

The drawing you see here is a trace I made with my pen on a sheet of Gateway paper. I did this with the intention of seeing it in stark black and white, the way it might have been 524 years ago. I left da Vinci’s neatly aligned and justified cryptic backward scrawl out of the illustration since its unintelligible to most of us and made no sense to painstakingly trace over.

There is a paragraph of text above the illustration that talks about Vitruvius’ measurements of the human body, which goes something like this:

Vitruvius, the architect, says in his work on architecture that the measurements of the human body are distributed by nature as follows: that is that 4 fingers make 1 palm and 4 palms make 1 foot, 6 palms make 1 cubit; 4 cubits make a man’s height. And 4 cubits make one pace and 24 palms make a man; and these measures he used in his building. If you open your legs so much as to decrease your height 1/14 and spread and raise your arms till your middle fingers touch the level of the top of your head you must know that the centre of the outspread limbs will be in the navel and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle.

The larger paragraph below it goes about breaking down the proportions of the entire human body, how the width of the hand relates to the distance between the elbow to the fingertips (a cubit), which relates to the entire width and height of the body.

From the roots of the hair to the bottom of the chin is the tenth of a man’s height; from the bottom of the chin to the top of his head is one eighth of his height; from the top of the breast to the top of his head will be one sixth of a man. From the top of the breast to the roots of the hair will be one seventh part of the whole man. From the nipples to the top of the head will be the fourth part of a man. The greatest width of the shoulders contains in itself the fourth part of the man. From the elbow to the top of the hand will be the fifth part of a man. From the elbow to the tip of the hand will be the fifth part of a man; and from the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be the eighths part of the man. The whole hand will be the tenth part of the man; the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man. The foot is the seventh part of the man. From the sole of the foot to below the knee will be the fourth part of the man. From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be the fourth part of the man. The distance from the bottom of the chin to the nose and from the roots of the hair to the eyebrows is, in each case the same, and the ear, a third of the face.

This drawing was something Leonardo da Vinci made for himself, it wasn’t something that he put on display or sold. In fact, it was only discovered many hundred years after he died. It was entirely the fruit of his passion for the human form, its shape and inner workings and a deep regard for geometry.

It is in a way a testament to man as God’s greatest creation. The man’s shape is inscribed in a circle and square; perfect shapes, as they are known. All the temples of the time used to be constructed with a square base growing upwards to a circular, domed top.

Another interesting feature of the drawing are the “two states of being” illustrated here. The horizontal span of the arms defines the relation of the body to the square and the angled limbs to the inscribing of the body in the circle. This representation of multiple states in one image is something we also see happening in idols and paintings of Indian deities. The intention there usually is to show off the various skills (handling assorted weaponry) and qualities (provider of wealth, learning) by representing them as a many armed God or Goddess.

The fact that da Vinci studied detailed dissections of the human form is quite a well known one. This internal knowledge of each organ, each sinew, muscle and bone is something that governs the position of every arc and line in this illustration. The subtle curvature of the bones of the legs, the tiny lines showing muscles and shapes gives what would otherwise be a simple diagram a much deeper sense of character.

The Vitruvian Man is the amalgamation of art, geometry, anatomy and science to create one of the most recognisable and iconic images of all time, which made this my first and only choice as an inspiration and foundation to this endeavour.

1 comment

Revati says:

Jun 1, 2011

Awesome. Welcome to cyber space!